WHEN THE WATERS RISE: STORIES OF STRENGTH FROM BAGOENGED

A Village Between Water and Land

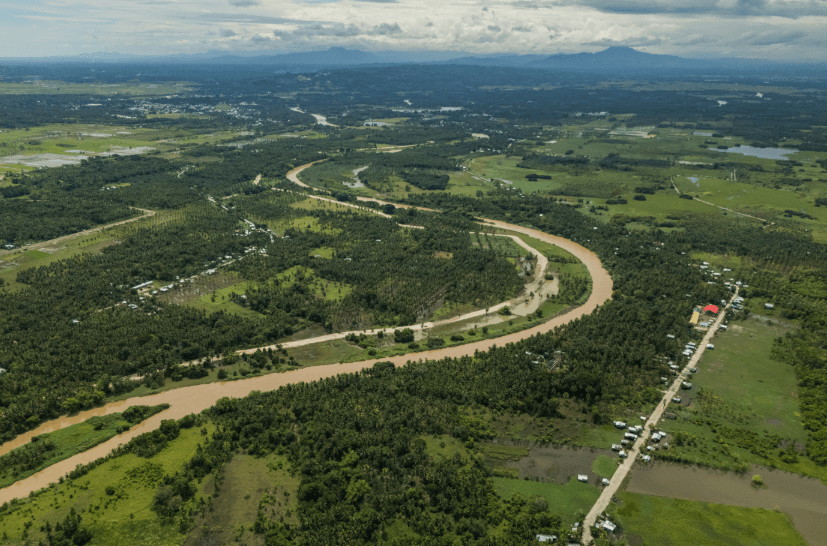

On the inland plains of Maguindanao del Sur, just 5.5 kilometers from Pagalungan’s town center, lies Barangay Bagoenged—a community shaped by history, self-reliance, and water. Nestled near the sprawling Liguasan Marsh, one of the largest wetlands in the Philippines, the community is surrounded by winding tributaries of the Rio Grande de Mindanao, a river that nourishes its fields and fishponds yet threatens its homes when the rains come.

In photo: An aerial view of the river surrounding Barangay Bagoenged in Maguindanao del Sur. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

Houses stand on stilts, connected by narrow wooden walkways. Children sometimes wade or paddle to reach the lone elementary school. Livelihoods depend on both the soil—over 2,100 hectares farmed for rice, corn, and coconuts—and the water, with over 1,200 hectares dedicated to fishing. But seasonal flooding, droughts, earthquakes, and occasional displacements from local conflict make life unpredictable.

In photo: ACCESS Team visits one of the houses in Barangay Bagoenged by crossing a narrow elevated pathway connecting the stilted house to the main street. (Photo by Alexane Simon for Action Against Hunger)

In Bagoenged, strength and hope are built in small, steady acts—by people like Mariam, the health worker who has served for decades; Pem, the young female leader who makes sure her voice is heard; and Abdullah, the fisherfolk learning to act before the waters rise.

In photo: Portraits of Mariam, Pem, and Abdullah. (Photos by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

Mariam: A Lifetime of Care

At 66, Mariam Abas, known to all as Babu Mariam, is as much a fixture in Bagoenged as its stilted houses and Balikakab trees. Her career in service began in 1987 as a daycare teacher, before she became a local health worker in 2000—a role she has held for 25 years.

“I want children to grow up healthy and have a future.”

— Mariam

In photo: Mariam prepares the oximeter to be used on one of the patients in the temporary health facility. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

Her devotion is rooted in personal loss. Years ago, her first child died from diphtheria despite being vaccinated. “Maybe I don’t want anyone here to experience what I did,” she says. “I want children to grow up healthy and have a future.”

After separating from her husband, she returned to Bagoenged to serve her own people. “I knew I wanted to be useful—to serve my own people, my own community. Because who will be more ready to serve your own people if it’s not you?”

In the early years of her career, she worked only as a volunteer. She would tend to her crops at dawn before fetching children for daycare or visiting households to promote health and sanitation without pay.

In photo: ACCESS team and a few residents of Barangay Bagoenged visit the old barangay health center. (Photo by Alexane Simon for Action Against Hunger)

Since Bagoenged lies in a low-lying area near major tributaries of the Mindanao River Basin, it becomes extremely vulnerable to frequent and intense flooding. Mariam shares that over the past decades, a cut-off channel diverted floodwater into the area, almost wiping the barangay off the map. With rainfall intensifying due to climate change, nowadays, floods go as high as an average person’s height, submerging homes, farmland, and health facilities.

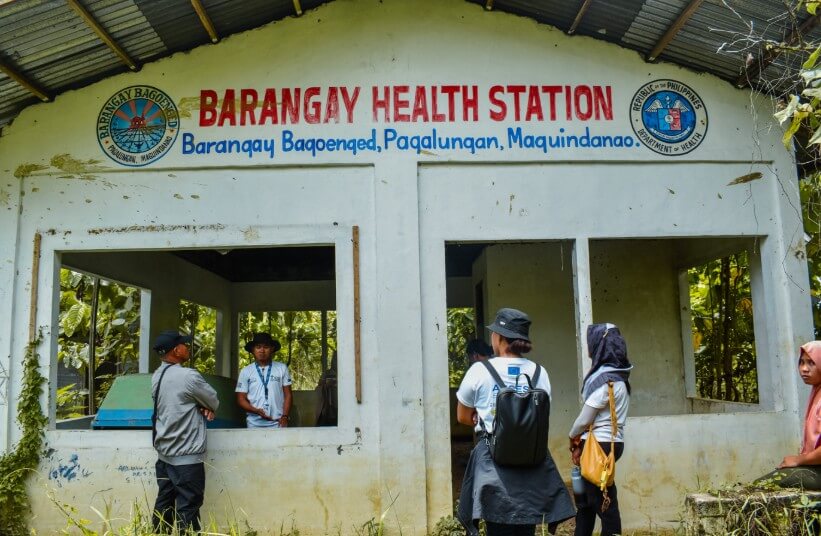

This tested Babu Mariam and her fellow health workers’ resolve. When the barangay’s original health center became unusable due to mud and water damage, Babu Mariam and her colleagues carried medical equipment from one house to another, setting up makeshift clinics in dry spots. For years, the community’s health station lay in disrepair, forcing residents to rely on the roving health workers.

This began to change when, in 2023, Action Against Hunger introduced the ACCESS project to the community. With support from the EU Humanitarian Aid, ACCESS helps communities, local governments, and civil society groups prepare for and respond quickly to disasters. The project’s goal is to ensure that communities like Bagoenged can access vital services like health care, clean water, sanitation and hygiene, education during emergencies, mental health & psychosocial support, and protection among others.

“Who will be more ready to serve your own people if

it’s not you?”

In communities like Bagoenged, this has meant rehabilitating damaged health facilities, providing essential equipment, and empowering residents through hands-on preparedness activities — ensuring they are not only recipients of aid but active partners in building resilience. Through the ACCESS project, a building was rehabilitated into a temporary health facility, furnished with a birthing bed, chairs, tables, a wheelchair, and life-saving kits. “Eighty percent of the barangay comes here now,” Babu Mariam says. “You can see now, people want to visit us often. A lot go here for check-ups, prenatal, and immunization. If we don’t know how to handle it, we refer them to hospitals. It seems every day is my busiest day.”

In photo: Mariam updates a health chart of one of their patients. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

Beyond providing health services, she teaches households how to purify water with charcoal, stones, and boiling—to prevent waterborne diseases. Moreover, she has tirelessly advocated for improved sanitation. “I lobbied to install toilets in the barangay, but they were lost in the floods.”

In July 2024, the worst flood hit. “In the worst flood, the water was higher than a person. I was on top of my house rescuing children and bringing them to safety. The first round of the flood took five days to subside.” Babu Mariam did not let this deter her. Rather, this urged her to give more input on the community’s disaster preparedness plans, building focus on addressing the health needs of the community in times of emergencies.

In photo: Mariam shows photos of the July 2024 flood to Action Against Hunger team member. (Photo by Alexane Simon for Action Against Hunger)

“A lot go here for check-ups, prenatal, and immunization. If we don’t know how to handle it, we refer them to hospitals. It seems every day is my busiest day.”

Babu Mariam shares how the knowledge she gained from participating in the training sessions helped her skills in disaster preparedness. Action Against Hunger launched a series of learning sessions as part of the ACCESS project to enhance local disaster response capacities. These efforts focused on equipping residents with essential emergency response and risk management skills. Babu Mariam participated in training sessions, covering the barangay disaster risk reduction and management plan, life-saving techniques, anticipatory and quick response, contingency planning, and early warning systems. “No other [organization] have done what you have done. And my training sessions are priceless. I might have spent thousands of pesos in school to learn all this, but ACCESS gave me this training. I learned so much—it’s priceless.”

In photo: On the left, Mariam and her fellow health worker talk about their patient’s check-up; on the right, Abdullah and his son wait for the health consultation to begin. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

When asked what she considers most important from all her years of working, she answers without hesitation: “Climate change. It’s real. We can’t stop it now—but we can adapt and learn to live with it. That’s what I teach now.”

Through the ACCESS project, she has found new tools to match her lifelong commitment, ensuring that the people of Bagoenged are not just surviving floods and hardship, but actively shaping a safer, healthier future—one that she hopes will outlast her years of service.

In photo: Mariam, whose hands have provided guidance and care to hundreds of families for decades. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

“Climate change. It’s real. We can’t stop it now—but we can

adapt and learn to live with it. That’s what I teach now.”

For Babu Mariam, the true measure of success is not only in the number of patients she has treated, but in the strength and readiness of the community she has served for nearly four decades. From cradling toddlers in her daycare to guiding young leaders, her journey reflects the heart of Bagoenged’s strength wherein generations learn from one another, standing together when the waters rise, and passing on the skills to face whatever comes next. In Babu Mariam, we are reminded that Bagoenged, shaped by history, carries forward the lessons of its past to prepare for the future.

PEM: LEADING WITH COURAGE

When Pembraida “Pem” Andoy-Santiago, 29, walks through Bagoenged, it is clear she knows almost everyone. Children wave, elders nod, and neighbors call her by name. She greets them in turn, asking about their families, checking on sick relatives, and sharing quick laughs.

In photo: Pem smiles, behind her are abundant water crops that sprung as a result of the area regularly being submerged to floodwaters. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

Whenever Bagoenged gets visitors, Pem would usually become their guide. She would lead them down the narrow wooden walkways between houses on stilts, pausing to point out the river—its slow, silty current the lifeblood of the community. “Most people here fish,” she explained, “but when the floods come, the fisherfolk still struggle.”

She passes by the old barangay hall and health center, now covered in thick mud, mold, and weeds. “Because these were constantly submerged, we grew tired of evacuating and moving the equipment over and over,” she recalled. “So, our leaders decided to rebuild elsewhere.” For years, there was no permanent health center—only roving workers who set up mobile clinics each day. “It wasn’t until ACCESS rehabilitated one of our buildings into a temporary health facility that our health workers finally had a place to stay and serve people properly. There are still plans to build a new permanent health center, but until funds come in, this one will do.”

In photo: Thick mud and overgown weeds cover the old barangay health center in Bagoenged. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

Reaching Bagoenged is never simple. During the rainy season, the road becomes a muddy track; in summer, it cracks and hardens under the heat. “The services provided by the municipality or province don’t always reach us,” she explained. Most offices and facilities are based in Poblacion, the town center, making it difficult for residents here to access them. “For us, it’s not just about whether services exist,” Pem told us, “but whether we can physically get to them in time.”

Pem knows the ins and outs of her community, as well as the struggles its people face. She knows how difficult it is for residents to access services, and that is precisely why she chose to take part in improving their systems and plans. This commitment led her to become part of the Barangay Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council, where she eventually joined the training sessions organized by Action Against Hunger through the EU Humanitarian Aid-funded ACCESS project.

In photo: Pem (wearing a hat and a brown jacket) accompanies the ACCESS team around the community of Bagoenged. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

“I want to save myself, my loved ones, and my community when disaster comes. Preparedness is everyone’s responsibility.”

— Pem

At the early stages of the project’s implementation, she stressed the challenges of responding to emergencies with limited resources. “We lack the funds to purchase early warning devices. Not every area in the barangay has [telecommunication] signal, which makes information dissemination so hard for us. For the meantime, we are using two-way radios, but we don’t have enough.” Despite this, she remained determined: “I want to enhance the community’s resilience and improve our disaster preparedness. Those are the goals I really want to achieve as part of the disaster risk reduction management council.”

Through ACCESS, Pem helped her community develop crucial plans—the Barangay Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Plan, anticipatory action plans for both flooding and armed conflict, and contingency measures that laid the foundation for early warning systems. For Pem, preparedness is not just technical—it is personal. “I want to save myself, my loved ones, and my community when disaster comes. Preparedness is everyone’s responsibility.”

In photo: Pem and Mariam make their way to the barangay’s covered court, as they prepare the health workers’ lunch for the day. Behind the is the temporary health facility rehabilitated through the ACCESS project. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

For many in Bagoenged, Pem is more than just a volunteer—she is a symbol of what young women can achieve in a community where leadership is often reserved for men. Bagoenged is a close-knit, Maguindanaon-speaking, predominantly Muslim community. Pem shares that for a young woman here, leadership is not easily earned. “[Our culture] is very patriarchal,” she says. “Often, men are given more value in governance… But I never believed I should stay quiet. Whatever men can do, I can do too—and sometimes even better.” But she admits it is not always easy, and that her education—a degree in Political Science and postgraduate law studies—helped strengthen her confidence and her voice in decision-making spaces.

Pem’s deep knowledge of Bagoenged also comes from a lifetime in public life. Her father was a community leader, and at 16 she became the Sangguniang Kabataan chairperson. She later served as desk officer for cases of violence against women and children. Despite being urged to pursue a political career, Pem shares she’s perfectly able to help her community and happy to do so without an official title. “I’m happy working in the [background],” she says. “It’s not required that I sit as chairperson or councilor just to be able to participate. I can still contribute in any way I can within the community.”

In photo: Pem and a fellow member of the barangay’s disaster risk reduction & management council (BDRRMC) having a discussion with ACCESS team member. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

“You have to trust yourself. People won’t have confidence in you if you don’t believe in yourself first.

Your only competition should be who you were yesterday. Be better today, and even more so tomorrow.”

Pem’s journey shows how leadership can take many forms—sometimes in the council room drafting disaster plans, sometimes walking visitors through the narrow paths of Bagoenged, or sometimes simply encouraging a young girl to believe in herself. In Pem, Bagoenged has not only gained a dedicated advocate for preparedness but also a voice that challenges barriers and inspires others, proving that true community strength grows when women are given space to lead.

“You have to trust yourself. People won’t have confidence in you if you don’t believe in yourself first. Your only competition should be who you were yesterday. Be better today, and even more so tomorrow,” she says as a message to young girls in her community.

Her persistence, confidence, and service have carved out a space for women’s voices in disaster preparedness and local governance. In choosing to lead not from a position of power but from a place of commitment, Pem has become a role model for young girls who see in her proof that leadership is not defined by gender, but by courage, responsibility, and a genuine desire to serve. Pem’s story mirrors Bagoenged itself: a community shaped by self-reliance, drawing on its own determination to meet challenges head-on.

Abdullah: A Fisherfolk Living Between Catch and Current

For Abdullah Dawadi, 49, fishing is both a livelihood and a lifeline. On a good day, he earns 500 pesos (less than 8 euros); on most days, closer to 150 pesos (around 2 euros). His small, weather-beaten boat and worn fishing gear limit his catch, even when floodwaters bring fish nearer. Yet like many in Bagoenged, Abdullah endures—adapting to the ebb and flow of a life shaped by the river.

In photo: Abdullah paddles his small boat along the river in Barangay Bagoenged, where fishing remains both a livelihood and a lifeline for many families. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

Bagoenged itself reflects the complex realities of life on the floodplain. At noon, children rush out of school, racing toward the nearest sari-sari or local sundry store, their laughter echoing past the stilted houses perched high above muddy ground. In the afternoons, men haul logs from the nearby marshlands, paddling through shallow canals in small wooden boats—the same boats they rely on for fishing. This way of life may look simple, but beneath the surface lies a complex reality.

In photo: Families leave their footwear on the road, right before the tree trunks that they would turn into bridges for their elevated homes. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

The community’s six sitios face overlapping hazards: seasonal floods that submerge homes and farms, prolonged droughts that parch crops, earthquake risks that threaten fragile structures, and local conflicts that occasionally displace families. Access to services and livelihoods is limited, especially when floods isolate the community from the main town center. “Here we have limited access to other livelihood options,” Abdullah says. “Sometimes our children go to school without eating. If they study outside the area, we can’t afford to support them. We don’t have a motorcycle. The broken bridge is also a big challenge, limiting the transport of goods.”

In photo: Three of Abdullah’s children spending time together inside their elevated home. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

But even in the face of inevitability, Abdullah believes preparation makes a difference. Through the ACCESS project, he joined community disaster preparedness drills. “I learned the importance of understanding early warnings to be able to do early evacuation,” he shares. “Now, we move our things to higher ground even before the floods come.” He hopes there won’t be another deep flood to test them, however, Abdullah says he feels more confident knowing what to do when disaster strikes.

“I learned the importance of understanding early warnings to be able to do early evacuation.”

— Abdullah

In photo: A sign showing the way to the evacuation center, which was installed in the community after the ACCESS community drill back in February 2025. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

Preparedness is only one part of survival. Health care is another. Abdullah and his wife regularly bring their children to the newly rehabilitated health facility in the community—a service that was unavailable just a few years ago, and a practice that families like theirs were not usually accustomed to.

In photo: Abdullah takes his youngest son to the temporary health facility for a regular check-up. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

“Before, health workers walked around without a schedule, and we had to go to the rural health unit, which is far,” his wife explains. “Now, basic health care is more accessible. Our children got vaccinated, and we visit whenever medicine is available.”

Abdullah navigates the river in Bagoenged, where fishing provides a livelihood but frequent floods continue to disrupt daily life. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

In moments like these, the threads of community, preparedness, and health are woven together. What ACCESS provided was not just a structure or a drill, but a framework that the people themselves, like Abdullah, put into action.

Abdullah’s narrative reflects what many in Bagoenged live every day—not resilience for its own sake, but the continuous work of adapting, learning, and strengthening systems so the community can face the next flood with greater security. As a fisherfolk, father, and resident of Bagoenged, he has seen firsthand how floods disrupt livelihoods, displace families, and endanger lives. Yet he has also seen how training, cooperation, and accessible services can turn vulnerability into preparedness. The ACCESS project brought vital support, but it is the community’s own resolve—families like Abdullah’s—that ensures these lessons endure. Abdullah’s story is a reminder that Bagoenged, shaped by water, continues to find ways to live with it, adapt to it, and prepare for what it may bring.

Full Circle: A Community Leading Its Future

Shaped by history, self-reliance, and water, Bagoenged has carried the weight of struggle. Now, these same forces have become the foundation of its resilience—one built not on endurance alone, but on agency, preparedness, and the shared strength of its people.

In Bagoenged, resilience is not just built by projects—it’s carried in the hands of its people; tied to collective action and not just enduring suffering. Mariam ensures health care is within reach. Pem ensures every voice is heard, including women, youth, and people with disabilities. Abdullah puts preparedness into practice at home.

The ACCESS project, funded by EU Humanitarian Aid and implemented by a consortium of partners, including Action Against Hunger, gave them tools, training, and facilities. But the determination to act comes from the community itself.

In photo: Balikjakab trees line the edge of Bagoenged, their roots gripping the flood-prone soil. (Photo by Martin San Diego for Action Against Hunger)

As the rainy season approaches once more, Bagoenged knows the floods will return. And when they do, its people will be ready—not only because of what they have endured, but because they have learned, together, to carry forward the lessons of their history, their self-reliance, and their life by the water.

FOR MORE ACCESS STORIES, VISIT:

www.accessproject.ph

The ACCESS Project (Assisting the Most Vulnerable Communities and Schools Affected by Complex Emergencies to Access Quality and Timely Humanitarian and Disaster Preparedness Services) is a multi-year initiative funded by EU Humanitarian Aid and implemented by a consortium of international and local partners, namely Assistance and Cooperation for Community Resilience and Development (ACCORD), Action Against Hunger, CARE Philippines, Community Organizers Multiversity (COM), Humanity and Inclusion Philippines, Integrated Mindanaoans Association for Natives (IMAN), Leading Individuals to Flourish and Thrive (LIFT), Mindanao Organization for Social and Economic Progress (MOSEP), Notre Dame of Jolo College Community Extension Services and Peace Center (NDJC), Nagdilaab Foundation, Pambansang Koalisyon ng Kababaihan sa Kanayunan (PKKK), and Save the Children Philippines.

Running from 2023, ACCESS addresses the complex and overlapping risks faced by communities in Mindanao and other parts of the Philippines, including recurrent armed conflict, natural hazards such as floods and droughts, and the growing impacts of climate change.